Picture-sources

Representations of ships form an important but difficult source for Viking-Age longships. This is particularly because those who originally created the pictures normally had other motives than a desire to represent the ships as true to life and in as great detail as possible. Often the ship was symbolic and quite anonymous – it only had to be present on the coin and to be recognisable as a ship. It was not necessary for it to resemble any particular existing ship – the situation can be compared with the symbols on traffic signs today. At other times the depictions may perhaps have been intended to represent a particular ship, e.g. Frey’s ship SKÍÐBLAÐNIR that had room for all the gods from Asgard, or William the Conqueror’s flagship at the invasion of England, MORA – but here the solution was to employ symbols that could identify the ship rather than to try to make a realistic delineation. This could also be difficult if the intention was to represent a ship that was itself mythological. If we ignore graffiti, it is apparently not until the Late Middle Ages that we in Northern Europe began to see attempts at realistic ship-delineations.

Different kinds of picture-sources

The ship-delineations appear in various contexts and hence also in different materials. The picture stones from Gotland are a group of textless grave monuments raised in the Germanic Iron Age and in the Viking Age that frequently show pictures of ships. They have often been discussed in connection with attempts to reconstruct the working of the sails in the Viking Age. The rune stones are also grave monuments but it is only a few of these that bear ship-motifs. Because of the material used, the degree of detail that can be shown on the stone pictures is normally poor. This is particularly the case with the pictures on the rune stones, since these were often hewn in granite.

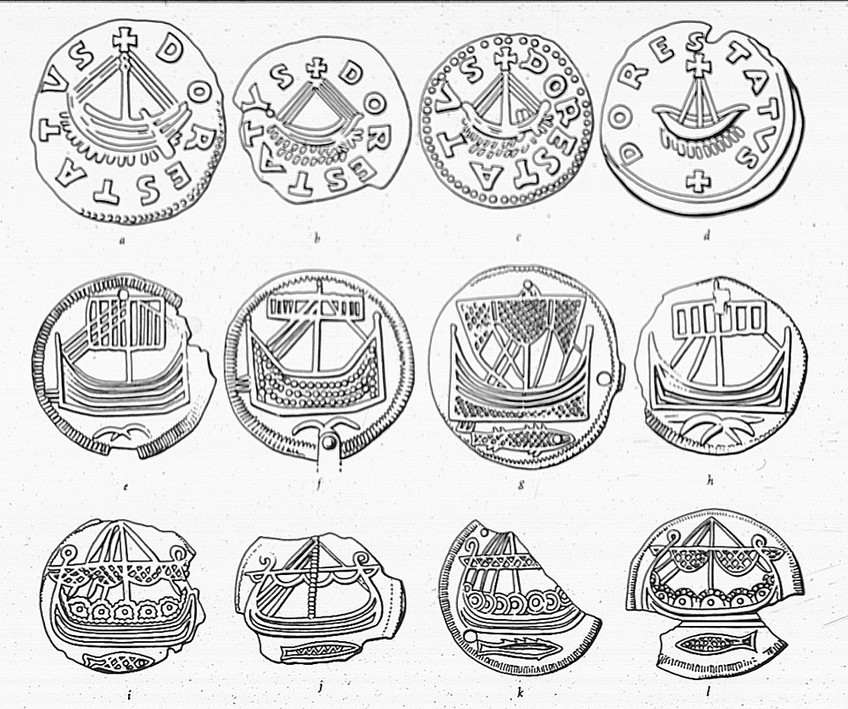

The coin pictures are perhaps the largest group but they show little variation between the individual pictures and the space on the coins is limited and does not allow much scope for refinements of shape or detail. It also has to be taken into account here that the coin representations are without doubt the most official and most regulated of the illustration programmes in which Viking-Age artists were engaged.

A very small group is formed by ship-representations on textiles, of which the Bayeux Tapestry is by far the most famous. This illustrated wall-hanging showing William of Normandy’s conquest of England in 1066 occupies with its details and lively scenes of shipbuilding and navigation a special place in ship-iconography, while other textile representations tend to be very stylised and subjected to the restrictions of the materials and the techniques.

Graffiti

The most varied and spontaneous picture material derives from graffiti, which are often carved in wood, more rarely hewn on stone. It is here seldom a case of representations of whole ships – often it is only the stems, the most conspicuous part of the ship, that are shown. We cannot, today, identify the background for the individual carvings and it is probable that the term ‘graffiti’ does not always do the pictures full justice – it is very likely that many of the carvings have had a definite religious or communicative intention and are not, therefore, as spontaneous and racy as they appear to be on the surface.

There is one characteristic that links all this large body of material: namely that there is not a single picture that we can identify as a full-length portrait of a great Viking-Age longship.

There are probably several reasons for this. The coin pictures, for example, are a ninth-century phenomenon and cannot therefore be expected to show the great ships. The same is the case with the Gotlandic picture-stones, which seem to come to an end in the tenth century.

An important reason, however, is without doubt the contemporary artistic convention that seems to prescribe that ships are to be seen from the side. The long, low hull of the longship with its disproportionately large sail was not in its natural shape attractive as a motif, while it was the fewest media and materials that offered the opportunity to indicate the number of oars and hence the size of the ship by depicting 10-30 shields or oars along the sides of the ship.